Key Takeaways:

-Businesses avoided tariff-driven price increases in 2025 through various temporary measure including front-loading and absorption of costs.

-Consumer prices may see a significant rise in the next year, which will reflect the real price impacts tariffs.

-Low-income households face disproportionate harm from tariff-related price increases.

The implementation of high tariffs throughout 2025 caused significant concern from economists and business owners on how taxes on imports could result in higher prices for domestically sold goods. The primary way this could occur is tariff passthrough, put simply, when suppliers of imported goods pass down import costs to American companies, who raise their prices in response, therefore placing the burden on consumers.

Supporting the argument are several research publications that analyzed the degree of passthrough during the 2018-19 US-China trade war and which concluded that incidence to consumers was almost absolute, meaning that effectively all of the increased costs from tariffs were borne by US consumers through higher prices on goods.

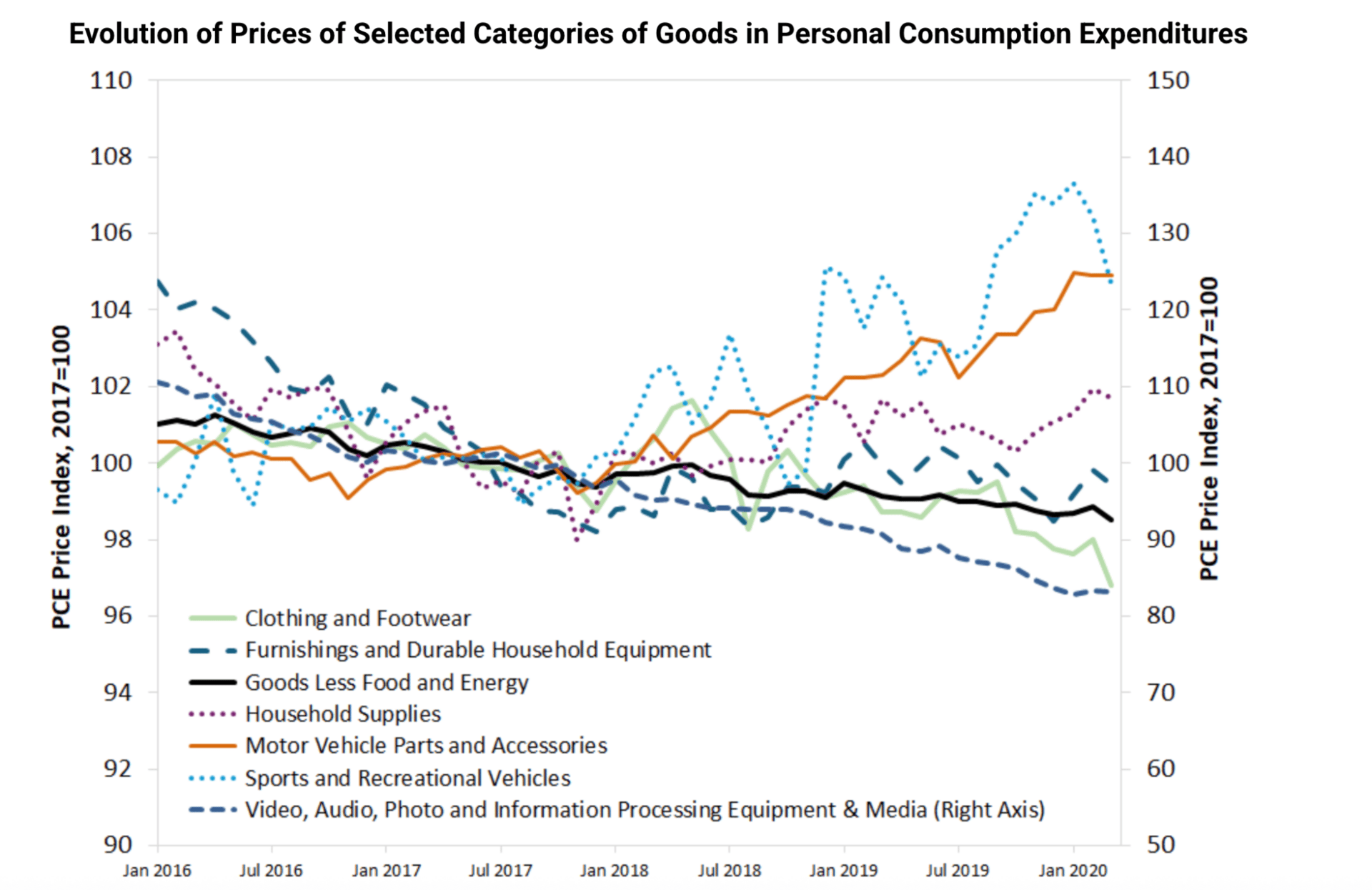

PCE price increases from 2016-2020, STLOUISFED

When the 2025 tariffs were announced, it was almost universally agreed among experts that there would be some tariff passthrough as a reaction to higher import costs. Yet, to the surprise of many, by the end of the year, the CPI, an index that measures the effective price change of consumer goods, saw a moderate 2.7% increase, mainly in food, gas, and utility costs. Similarly, the US saw an annual inflation rate of 2.7%, although it’s important to note for both figures that the government shutdown left significant gaps in data.

Following the release of the statistics, major media headlines broadcasted the muted impacts of tariffs on prices, supporting the sentiment that, at least for average American consumers, tariff passthroughs weren’t drastic.

The low degree of passthrough to prices in 2025 could reflect the relatively early knowledge that tariffs would be implemented in some form during 2025, as tariffs were a key campaign promise of the Trump Administration’s election, rather than a surprise as seen in the last trade war, which gave most firms time to strategize for import duties.

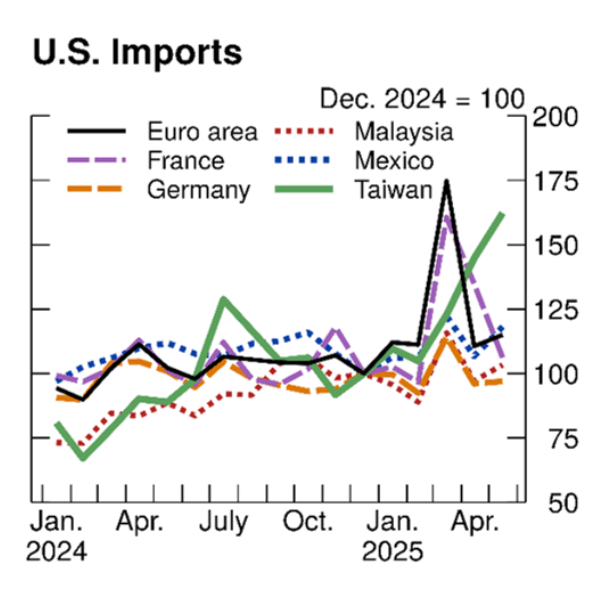

Additionally, several effective tariff-mitigation strategies were used by American companies—although many of them were short-term fixes rather than long-term adjustments. One such strategy was price discrimination. Another, bearing more significance for the future of prices, was front-loading—when companies stockpile inventory ahead of tariffs to temporarily circumvent paying import costs. There’s substantial evidence that many US firms front-loaded ahead of the official start of the April 2nd “Liberation Day” tariffs.

Import Volume from International Countries, FED

Front-loading itself isn’t a harmful act—in fact, it can be seen as a rational economic response to higher future tariffs. However, stockpiling of inventory by US companies as a buffer against raising prices means that the true cost impacts of the tariffs are delayed until after the inventory is substantially depleted. Thus, tariff impacts on CPI and inflation by the end of 2025 don’t reflect the actual degree of passthrough that will be seen under prolonged tariffs.

Another important factor of passthrough is uncertainty. The renegotiations and rollbacks in the wake of the “Liberation Day” tariffs have driven unprecedented economic policy uncertainty. One of the main impacts as a result is that US business investment has been constrained, as companies have faced several difficult questions: is it rational to make a bulk supply order when tariffs on the items might be reduced in the near future?

With the administration’s tariffs being applied much more broadly over countries in the global markets, what’s the cost-benefit of building new supply chains to circumvent tariffs when a new source country might get tariffed later? Most importantly, in regard to tariffs' goal of bringing back domestic manufacturing and competitiveness, what’s the risk of multi-year domestic infrastructure investment when tariffs may change on a whim and send competitiveness back overseas?

These relatively unanswerable questions have driven many US companies to opt for a route safer than being the first to raise prices or making risky supply chain adjustments: absorbing the losses. Molson Coors cut 2025 earnings outlooks significantly, citing “‘higher-than-expected indirect tariff impacts’” on aluminum, with the earnings cut representing absorption of losses rather than passthroughs. Costco, with ⅓ of sales being imported goods, announced that it “sought to minimize price increases on “staple items” such as fresh fruits like pineapples or bananas that were imported from the same regions, even if that reduced the company’s margins.”

Absorbing losses to delay price may be the most rational choice in the short term. However, as earning quarters pass, US companies will eventually be forced to face the choice between growth and raising prices. Moreover, the strategy is disproportionately beneficial to large corporations, who have the advantage of institutional partnerships and capital-raising opportunities. Small businesses, on the other hand, don’t enjoy the same luxury. In fact, a recent CEO survey found that 57 percent of small- to medium-sized businesses plan to raise prices over the next three months, and 8 percent anticipate increasing prices over 10 percent.

The importance of understanding the buffers to real tariff-driven price increases can’t be understated when evaluating a tariff’s impact on the American population. For one, the substantial macroeconomic impacts that tariffs will have on the economy could certainly put a drag on economic growth. JP Morgan Global Research estimated a 35% probability of a U.S. and global recession in 2026, with inflation being a significant factor.

At the consumer level, tariff-driven price increases could have pernicious effects on lower-income households. Around 50 million Americans were found to be low income (having household incomes below 125% of the poverty threshold), and 35.9 million in poverty. Data shows that groups in poverty see higher rates of disease, mortality, and disability. When considering the poverty distribution in America, with almost 1/6th of Americans

With consumer expenditure data from Brookings finding that low-income households spend 83% of their annual income on basic necessities—housing, food, and transportation—tariff-driven price increases could cause substantial decreases in health outcomes and increased risk of mortality.

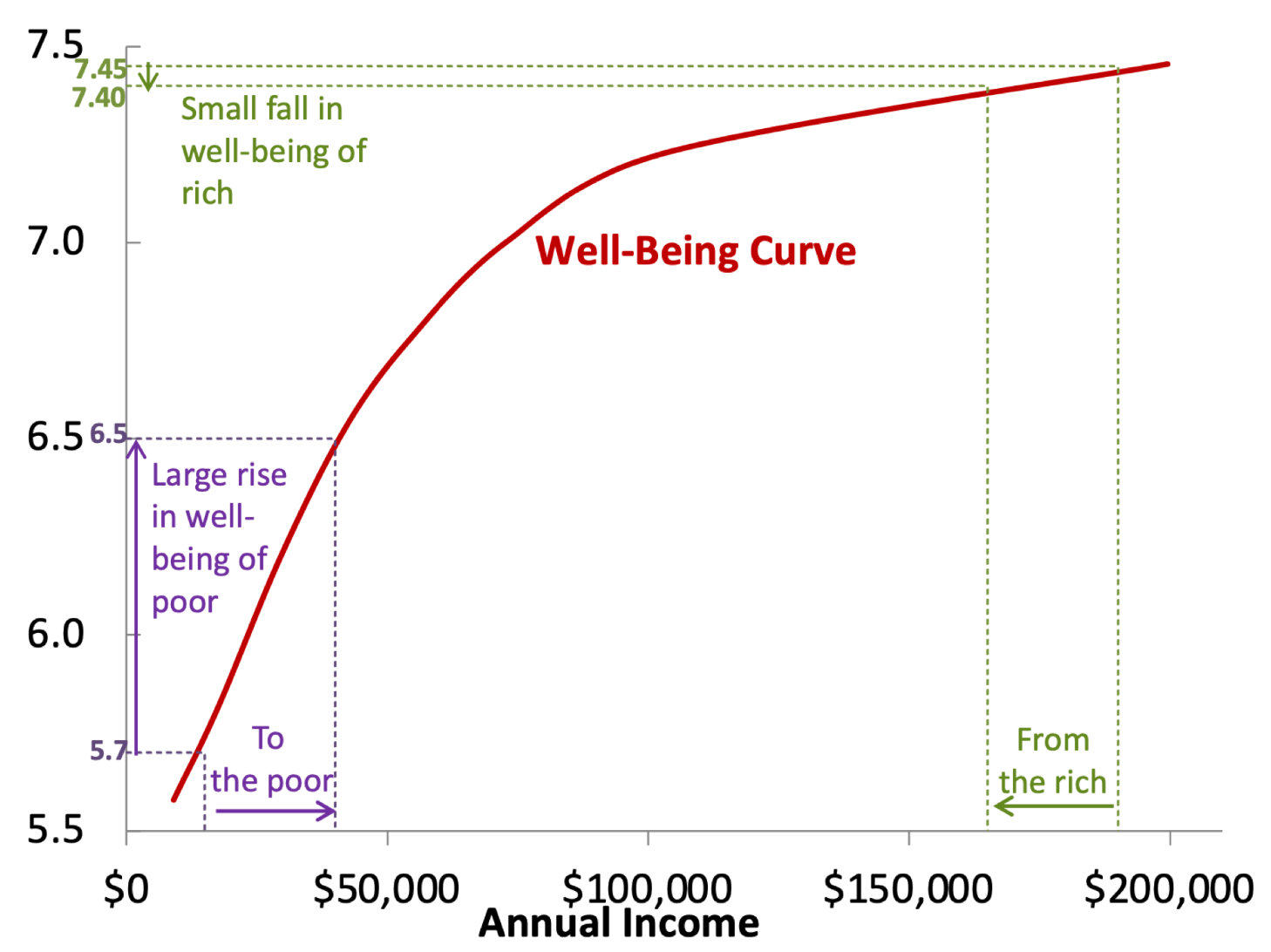

One of the simplest ways of illustrating how price changes can disproportionately impact groups in poverty is the well-being curve.

The well-being curve reflects data points from survey research, undoubtedly highlighting how even a marginal decrease in income is associated with a significant drop in well-being among lower-income groups. With tariff-driven price increases effectively reducing the amount of available income of households while providing them the same benefits as before the tax, it stands to reason that tariffs could cause significant impacts to the wellbeing of the most vulnerable sector of American society. Moreover, among that population, a disproportionate amount are minority groups, with 26% being African American and 23% Hispanic.

The Bottom Line

Although CPI and inflation reports are driving sentiment that tariff impacts on prices are moderate, significant front-loading and cost absorption by American companies are delaying the long-term price impacts of tariffs. Tariff-driven price increases could lead to substantially worse outcomes in terms of the health, security, and well-being of low-income households and people in poverty. Ultimately, it’s crucial to consider how tariffs and resultant price increases can disproportionately impact lower-income households and minority groups in America.